The Major Scale

The major scale is one of the most basic and foundational topics in all of music theory.

Whether it’s classical, jazz, or any popular music style/genre, music is filled with the sounds of this scale. Classical music in particular, from around 1650 until 1900, was based mostly upon major and minor scales. (We’ll get to minor later.)

It continues to be possibly the most-used scale in popular styles nowadays, including alternative, rock, pop, dance… you name it. As we increase our listening skills, we’ll start to appreciate the huge role it plays in music. (We’ll also be much better prepared to make our own music in whatever style we choose)!

A huge side benefit of learning the major scale is that it will serve as a springboard for learning tons of other music theory. This includes topics like minor, modes, intervals, chords, exotic scales, and more. We can think of the major scale as our “default” scale, allowing us to see the variations of other scales in comparison to it.

We’re here to break it all down for you, nice and easy, and really explore and understand this subject, once and for all.

Introduction: The Scale

A scale is a specific pattern of notes, usually half-steps and whole-steps, that covers the span of an octave. Common scales often have 7 different notes, but there are also many scales with different amounts of notes, including 5, 6, 8, etc.

A scale can start on any note. Therefore, for every type of scale there are 12 possible starting notes. The name of the scale is the same as the starting note – so we could have the G minor scale, or the Bb major scale, for example.

The major scale is a 7-note scale, made up of a specific combination of half steps and whole steps. (As a quick review, a half step is the very next note on a piano away, a whole step is two notes away. Two half steps equals a whole step. Check out the lesson on semitones for a refresher.)

Emotional Quality

Take a listen to the sound of the scale:

The major scale is often described as sounding “happy”, or being associated with positive emotions, especially when compared with the darker, more serious sounding minor scale. But keep in mind, there are no rules as far as musical emotions go; take a listen, and decide for yourself!

Here’s an audio example comparing the sounds of major vs. minor. First, a major scale is played up and down 2 across 2 octaves, followed by the same thing in minor. (Then the entire thing is repeated.)

Scales Vs. Real Music

How are scales used in music?

When we study or practice the major scale, we’re dealing with it all by itself, without any musical context. However, when it comes to actually making music, we don’t just play the notes of the scale up and down in order, like somebody practicing on their instrument! That would make for some pretty boring music.

A scale is a source of notes; like an alphabet. The notes can be rearranged in any order, they can be repeated as many times as you want, and not all the notes have to be used. Also, the notes can be performed on any instrument, or sung by any voice, in any style of music, and with any rhythms and tempo (speed).

Making music by simply playing a scale in order, note by note up and down, is actually the most boring way to arrange notes in a scale. This would be like trying to have a conversation with your friend, and all they do is recite the ABC’s in order. An alphabet can be the source for great poetry, humor, stories, dialogue; but only if the letters are arranged in an interesting way. The letters form words, the words form phrases, the phrases form sentences. Music is exactly the same; notes form musical phrases, which form musical sentences, etc.

The number of possible emotions that can be evoked from the major scale are endless. In a real musical context, a melody in major can be sad, heroic, goofy, calm, powerful, optimistic, reminiscent, and many other possible feelings. It doesn’t have to always sound like the songs being played by your neighborhood ice cream truck.

It’s still very important to learn scales in order, up and down, because that’s how we memorize them in the first place. ABC’s might not be very interesting conversation, but they’re still the first thing we need to learn when we start studying the English language.

The Major Scale Pattern

Every scale has its own individual pattern (usually of half steps and whole steps). This pattern is what makes a particular scale unique.

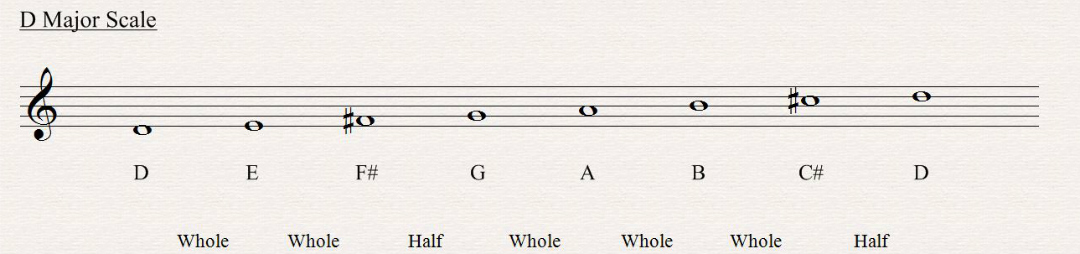

Starting on any note, we can build a major scale by using the following pattern:

Whole, whole, half; whole, whole, whole, half.

Try saying it out loud a few times to get the hang of it:

Whole, whole, half; whole, whole, whole, half.

Whole, whole, half; whole, whole, whole, half.

You can memorize this almost like a song, or poem, and recite it while walking down the street, or on line at the grocery.

It’s 2 whole notes followed by a half, then 3 whole notes followed by a half. It’s not really rocket science.

Building a Scale

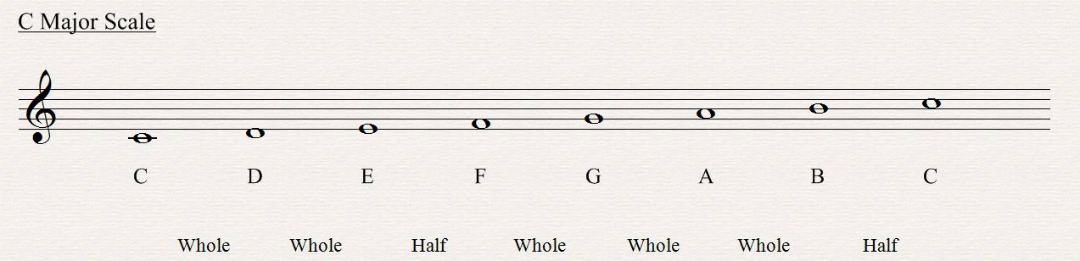

Let’s do an example. Our starting note will be C, so the name of this scale is going to be the “C major scale”.

To find the rest of the notes other than C, we simply use our pattern. What was it again? Oh, yeah, whole, whole, half; whole, whole, whole, half.

So our pattern tells us that the next note after C is a whole-step up. That’s the note D, which is a whole step (2 half steps) away from C.

C D

Next we need another whole step up from D; that’s the note E.

C D E

Next we need a half step (remember, whole, whole, half). A half-step up from E is the note F.

C D E F

Now that we have the hang of it, we can do the last 4 notes a little more quickly (whole, whole, whole, half). From F, a whole step up is G, another whole step is A, yet another whole step is B, and finally a half step up from B which is back to the note C again:

C D E F G A B C

So, we started on C, and we also ended on C. The major scale is known as a 7-note scale, because it has 7 different notes; but the truth is, it’s really 8 notes all together, since the last note duplicates the first note.

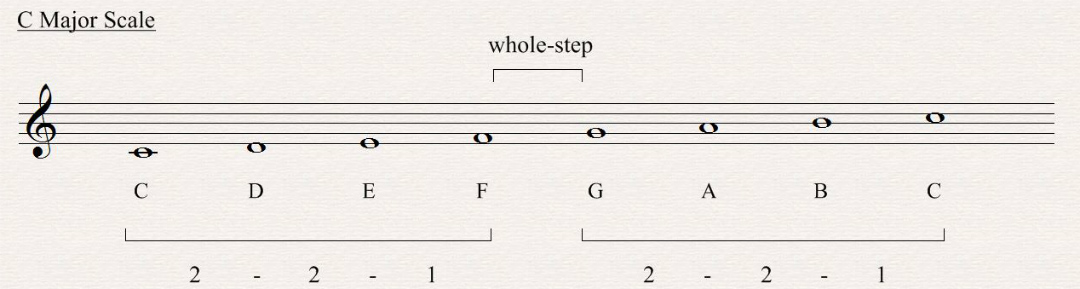

Here’s what this looks like in music notation (in treble clef):

Other Keys

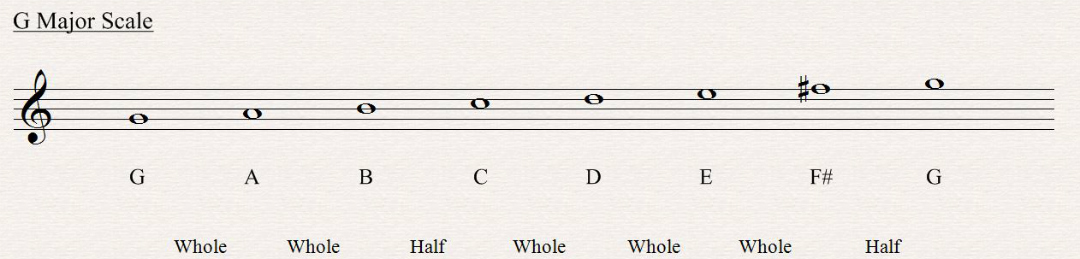

Of all the major scales, C is the easiest, since it’s made up of only the white keys. In order to build a major scale from any other note besides C, just follow the exact same procedure. Choose the starting note, and then just apply the pattern (which by now, we’re getting quite familiar with).

Here are some examples of the major scale in other keys:

In G:

In D:

Scale Degrees

Every note has its own special position, or placement, within a scale. For example, F is the 4th note in a C major scale, D is the 2nd note, and G is the 5th note.

The various positions within a scale are known as scale degrees. So for example, we could refer to “the 1st degree of the scale”, “the 5th degree of the scale”, etc. Picture a ladder with 8 rungs; each scale degree, or rung, has its own individual place within the scale.

Each scale degree has its own unique sound. The 1st degree has a certain sound, the 2nd degree has its sound, etc. It doesn’t matter what key we’re playing in – what matters most is what position each note is in relation to the current scale.

In other words, when we listen to music, we pay much more attention to where each note is in the scale, than on which particular note we’re listening to. Unless you happen to have a somewhat rare ability called absolute pitch (or “perfect” pitch), you can’t even tell what note you’re listening to without checking on an instrument. But you can tell where you are in the scale just by listening (with practice).

Musical Syllables

Solfege, or the solfege system, is a system of musical syllables which you may recognize from the famous film “The Sound Of Music”. The movie, however, did not invent these musical syllables; the solfege system has been around for a very long time.

(There are actually different forms of this system, we’ll be working with what’s known as the moveable-DO solfege system, just like in The Sound of Music.)

The syllables for major are DO, RE, MI, FA, SO, LA , TI, DO. (That’s pronounced doh, ray, mee, fa, so, la, tee, doh.)

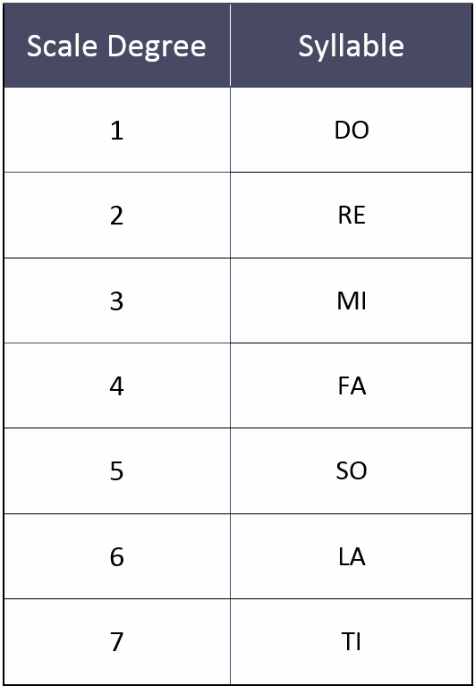

Each syllable corresponds to a scale degree. The 1st degree of the scale is DO, the 2nd is RE, the 3rd is MI, etc. Here’s a chart for the syllables:

So, for example in the key of C major, G is the 5th degree (C, D, E, F, G…); therefore the correct solfege syllable is SO. D is the 2nd degree, so its solfege syllable is RE, and so on.

The advantage of these syllables is that they’re so easy to sing. And being able to sing the notes of scales is really crucial if someone wants to improve their musical ear. Solfege syllables are probably the most effective way to learn the sound of scale degrees (which will go a long way toward improving your overall musical ability).

Traditional Scale Degree Names

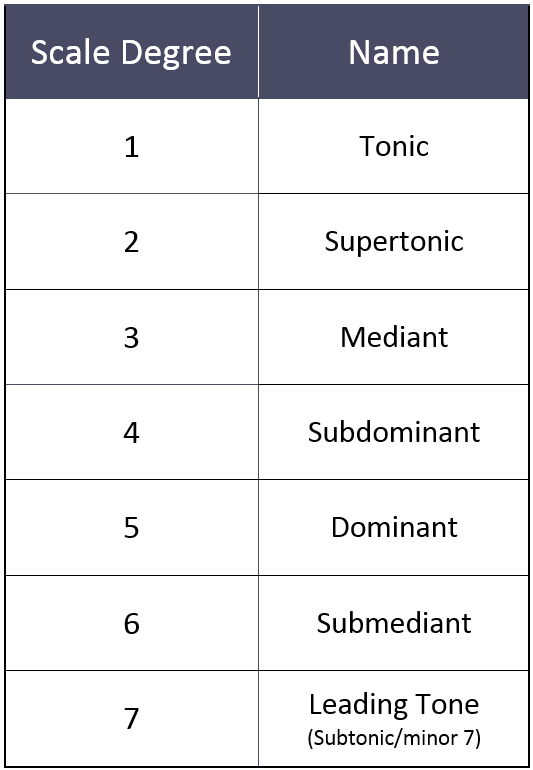

Scale degrees also have sophisticated names that can be found in many harmony textbooks. These are especially useful in the study of classical music. But don’t worry if these names seems intimidating to you, they’re more afraid of you than you are of them!

Actually that’s not true, you’re much more afraid of them. Anyway, it’s not really necessary to memorize all these names, but a couple of them are important and are used all the time. So here they are in order:

The most important names to remember from this list are tonic (the 1st degree), subdominant (the 4th degree), and dominant (the 5th degree).

The name of the 7th degree actually depends on the particular scale. It’s only called “leading tone” in scales like major, where the 7th degree is a half step below the 1st degree. Otherwise, it’s known as “subtonic” or minor 7.

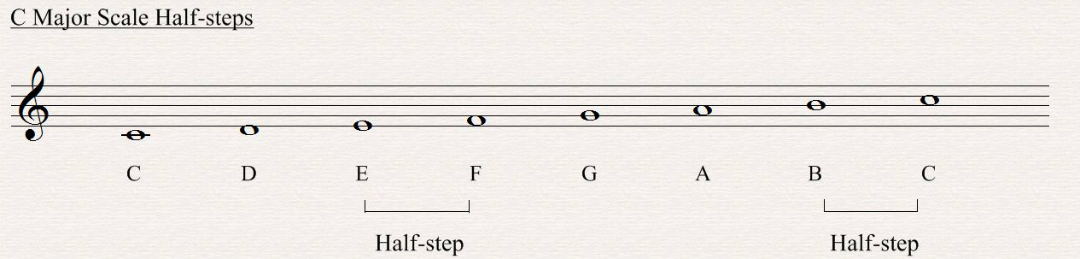

Importance of the Half Step

There are only two places in the major scale where there is a half step between adjacent notes; this occurs between the 3rd and 4th degrees, and between the 7th and 1st degrees. All the rest are whole steps. This another good way to picture and remember the major scale:

It’s also important for another reason – these half-steps are the most recognizable way to hear the major scale. In other words, it is the placement of these half steps that help our ears recognize when we’re listening to a major scale (or what it’s not a major scale). All the rest of the notes in the scale are whole steps, so whenever our ears hear a half step, we notice it!

Here’s an audio example demonstrating the sound of these half steps:

Each type of scale has its own special placement of half steps. Only the major scale has the half steps placed at these particular points, between 3 and 4, and between 7 and 1. These half steps literally define the sound of major.

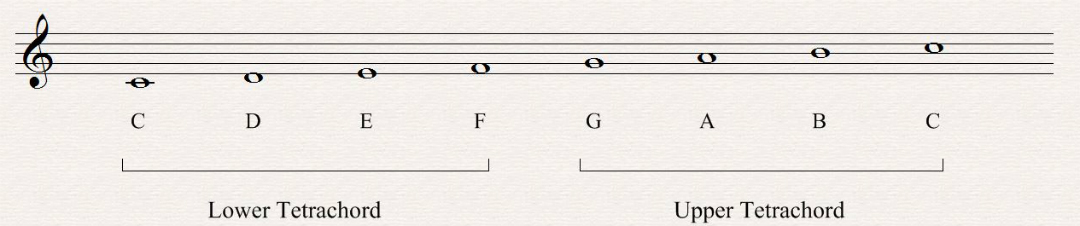

Half the Scale It Used to Be

One final area to discuss about the major scale; this time we are going to slice it in half! (Don’t worry, no major scales were harmed in the making of this lesson.)

The musical term for half of a scale is a tetrachord. It is a specific pattern of 4 notes, usually separated by whole or half steps.

The major scale can be broken into two tetrachords, an upper one and a lower one:

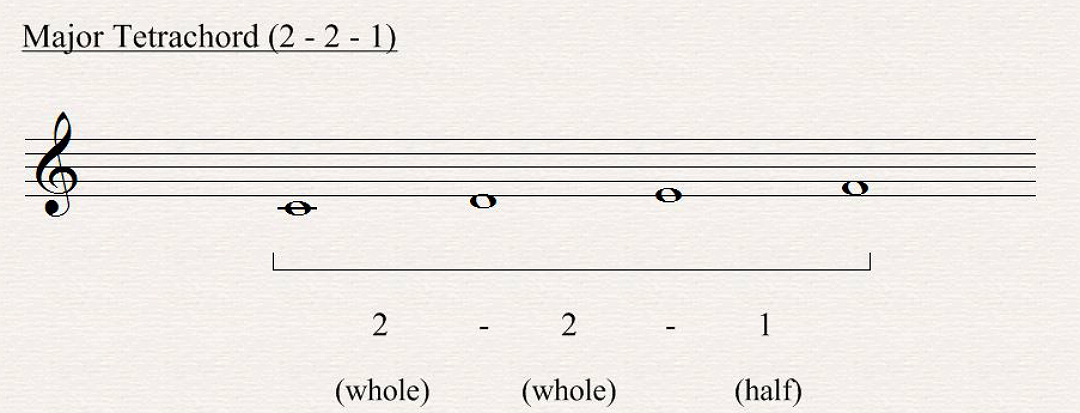

If we look carefully we can see that both tetrachords are identical. Each has the following pattern: whole, whole half. Instead of words, this time we’re going to use numbers, and call it a “2-2-1”. (The numbers here represent the amount of half steps, so 2 means 2 half steps, or a whole step. 1 means a single half step.)

A tetrachord with the pattern 2-2-1 is known as a major tetrachord.

The major scale consists of 2 major tetrachords, separated by a whole-step the middle:

This is a great way to think of and visualize the major scale. Nothing but two identical 4-note chunks joined together.

Practice Quiz

Major Scale Quiz

Test your knowledge of this lesson with the following quiz:

Image Attribution:

practice makes perfect. by Jukie Bot ©2013 CC BY 2.0

289/365 – 07/14/10 [365 Days @50mm] – ABC’s by Shardayy ©2010 CC BY 2.0

Pauline climbing wooden ladder on Putucusi by Jimmy Harris © 2009 CC BY 2.0