Music Note Names:

Organizing the Notes

So far, we have learned the music note names for all the white keys on the piano, and we’re well on our way toward mastering the piano keyboard! Now that we have a clearer understanding of musical pitch and how it relates to the piano, in this lesson we’re going to learn a simple but extremely useful system that will help us organize note names in a much more manageable way.

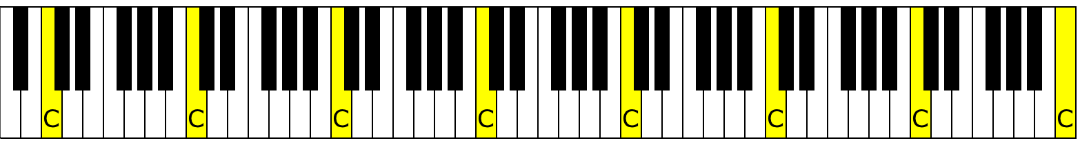

In our study of note names so far, we’ve noticed that there is more than one C note on a piano. In fact, there are a grand total of 8 of them on a full 88 key piano. So how in the world are we supposed to tell them apart?

Imagine a family where everybody has the exact same exact name; maybe if you’re George Foreman then this doesn’t bother you, but personally I would find it kind of confusing.

What we need is a way to pinpoint which note we are referring to. The best place to start is by examining a note that already has its own special name: middle C.

Middle C

If you have ever taken a piano lesson before, or tried to learn to read notes, chances are you’ve come across the term “middle C”.

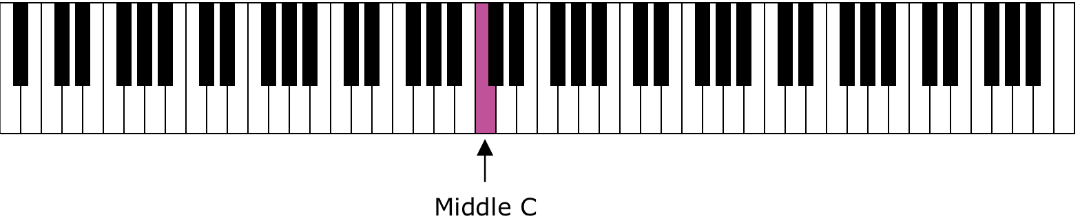

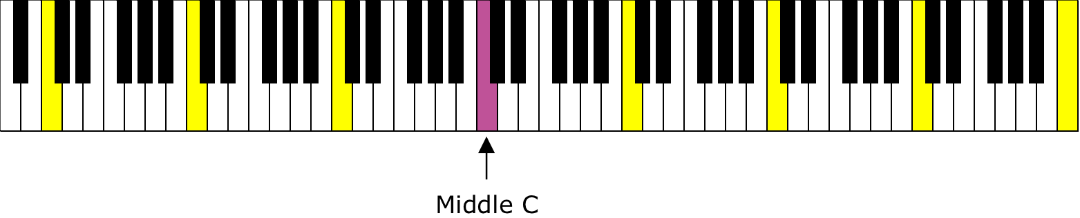

Middle C is a specific name given to the C note closest to the middle of the piano. Middle C is the 4th C up from the low end of a piano (the left side), and the 5th C down from the high end (right side):

Here we have all the C’s on the keyboard (shown in yellow), with Middle C displayed in purple:

Why Does It Matter?

Before we continue, let’s just clear something up for a moment. Do we really care which C we are playing? We learned earlier that all notes an octave apart have the same basic sound. So does it really matter if we play one C as opposed to another? Won’t the music basically sound fine, as long as we play the right note names?

The truth is, it does matter, because to some extent it does change the sound. Even though octaves all sound like variations of the same note, they certainly don’t sound exactly the same. Each octave is lower or higher sounding than the next, and this alone can make a big difference in the sound.

Let’s take an example – here’s that famous heavy metal classic “Mary Had a Little Lamb”, first played in the middle register of the keyboard, and then played all the way down at the low end of the keyboard:

Same song, but it sounds quite different in another octave, doesn’t it?

In this example we moved 3 octaves away from the original, but even a one-octave change in either direction still changes the sound in a noticeable way. So that’s why we have to know where we are on the keyboard.

That doesn’t mean that one way is the right way and one way is the wrong way; it just depends on how we decide we want it to sound. It’s similar to deciding if you want to have your song played by flute, guitar, or sung by a choir – the song is still the same song, but it will sound very different depending on the choice of performer(s)/instrument. Which we choose is up to us.

So in the above example, obviously the first version played in the middle of the keyboard would probably be the more typical and natural choice, but if we wanted some kind of disturbing horror movie version in which the lamb wins, then perhaps we would choose the second version.

Being Literal

When we read sheet music, whoever wrote the music has already made a decision about which octave the notes should be played in. Do we have to take their instructions literally and play it in that exact octave?

Well, it depends on the particular situation. Sometimes, the exact octave actually does not really matter – i.e. the music would sound perfectly fine in a different octave, too. Other times, it matters a lot. Whether or not we should follow the sheet music exactly is a judgment call, depending on the situation or the type of music.

For example, a simple lead sheet of a pop song doesn’t normally have to be played in the exact octave in which the music is written. In that case, the sheet music is just supposed to be a general set of instructions on how the tune goes. But if we are playing in an orchestra, I wouldn’t suggest trying to play your oboe part in a different octave than Beethoven wrote down; the conductor or teacher probably won’t be too pleased with that! (Classical music is intended to be played exactly the way it’s written.)

Here’s the point of all this: we do need to at least be aware of which octave we’re in. And that’s why there’s such thing as middle C – to help us know where we are on the keyboard. Middle C is a reference point. For example, if we say “the D above middle C”, everyone knows exactly which D note we’re referring to; the one that is directly to the right of middle C.

Music Note Names – Scientific Pitch Notation

Okay, we’re definitely headed in the right direction! We have a name for one of the C’s (middle C), so that’s 1 down, 7 to go. But we still need a name for all the other C’s, so that we can tell them apart from one another.

Thankfully, there is a simple system for organizing music note names known as scientific pitch notation. The name might remind you of math problems you had in elementary school with long numbers and decimal points, but have no fear; this has nothing to do with that. It’s a really simple way of numbering the notes by their specific octave.

Here’s how it works:

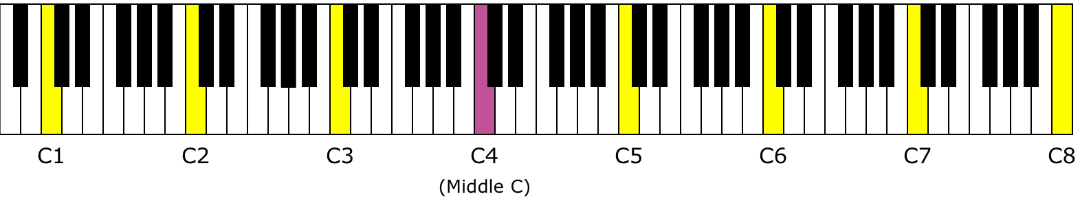

The lowest C on the keyboard (the third white note from the end) is called C1. From there, each C to the right increases by one, so next we have C2, then C3. Then comes middle C, or C4 (those two names are interchangeable). Then C5, C6, C7, and finally the very last note on the keyboard, C8, all the way on the right:

There may be other music note naming systems in existence, but this method from the Acoustical Society of America is probably the most widely accepted (and it avoids dealing with negative numbers such as C-2).

So at this point, we have a way to refer to a note, like C2, and know exactly which C we’re talking about. This is much better than saying, “the C that’s pretty low, but not the lowest one, know what I mean?”.

Octave Registers

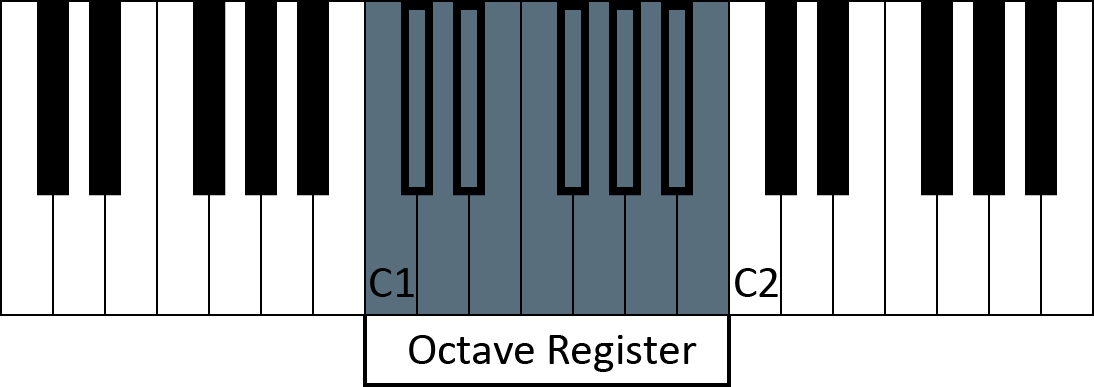

Okay, so we know how to name all the C’s on the piano by octave. Well, what about all the other notes besides C? In order to number musical note names properly, we must understand octave registers.

Remember how we learned in the very first lesson all about the 12-note patterns that make up a keyboard? From now on, we’re going to call these 12-note patterns octave registers – because they cover the span of an octave, and “register” just mean a span or area of pitches.

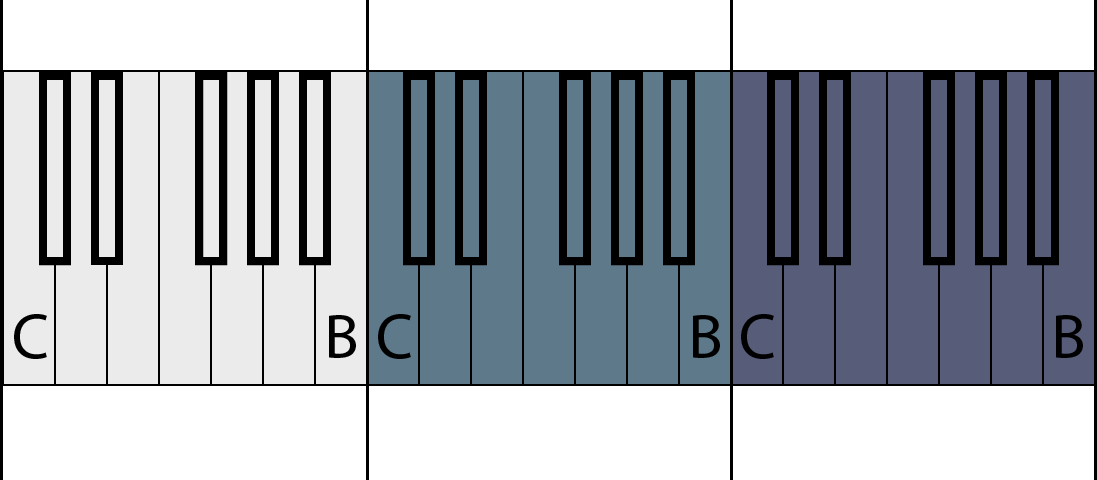

Each octave register extends from C up to B. The next C then starts the following octave register:

So for example, from C1 up to C2 (but not including the note C2) is its own octave register. (This is the lowest complete octave register on the keyboard.) Similarly, from C2 up to C3 (again, not including C3) is the next octave register, and so on:

With this in mind, we’re ready to learn the key to organizing music note names properly:

All of the notes within a particular octave register are labelled with the same number.

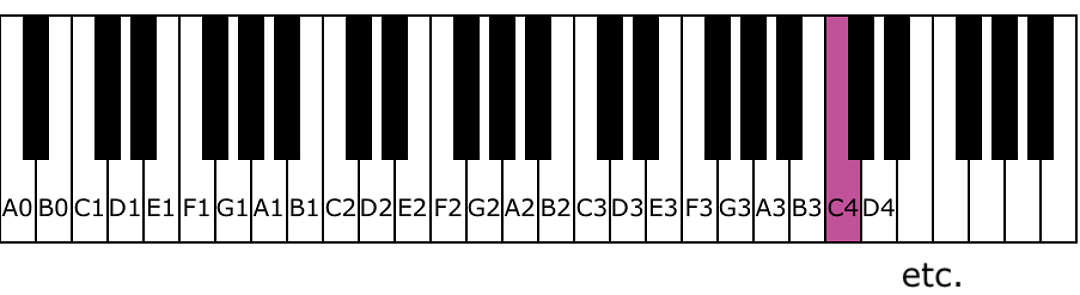

So for instance, all of the notes between C1 and C2 are labelled with a 1. So from left to right, it goes: C1, D1, E1, F1 , G1, A1, B1, then the next note up is C2. Then D2, E2, F2, G2, A2, B2, C3, D3, E3 etc. I could go on, but I think you get the idea. Each C starts a new octave register and gets a new number.

What about the notes below C1?

Those notes simply get a zero after them. A0, B0, then C1 (because every C begins a new octave register), D1, etc.

Here are the music note names labelled on the keyboard:

Taking a little bit more time at the beginning to learn the notes this way is so worth it. In fact, learning notes just by their names, without any sort of reference to which octave they’re in, is pretty much “doing it the hard way” in the long run. Learning it correctly from the start will save us a whole lot of frustration down the road!

One more thing, remember that we don’t always have to call notes by their number name e.g. F6, if the particular octave register is not important in that situation. Sometimes we just call it F and leave it at that. But if we know how to name notes properly by octave, we’ll be able to get specific if we need to.

Practice Worksheet

For some practice on music note names, check out this pitch notation worksheet.

Image Attribution:

Organized by Uwe Hermann ©2006 CC BY-SA 2.0

C64 Orchestra 2008-01 by Arnoooo ©2008 CC BY-SA 2.0

practice makes perfect. by Jukie Bot ©2013 CC by 2.0